"It's half-cooked," or "It's burnt."

Cooking was a harder test. I had to cook rice, dal, and vegetables at the same time in different compartments of the triple-boiler. Furthermore, I had to turn on the flame just before going to massage Srila Prabhupada, and when I returned after the massage?presto!?everything was supposed to be perfectly cooked.

I would cut up all the vegetables at about 11 A.M. and put them into the boiler along with rice and dal. The dal (split-pea or mung) went in the bottom pot along with water and spices. Cut vegetables went into pot number two. And in the top pot I placed a double-decker tin, with rice and water on the bottom and zucchini slices on top.

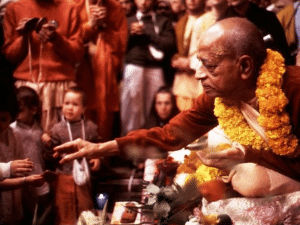

The first few days in Los Angeles, Srila Prabhupada came into the small room where I worked and stood beside me, showing me how to cook. He demonstrated the proper texture for capati dough, making it as soft as possible. It didn't matter if the dough was wet, he said, because you could add flour to each patty while they were being rolled. Prabhupada also showed me how to spice and how to make an instant version of sweet rice.

Each day when the massage was over I would dash back to the boiler. My biggest problem was the rice. Being in the top pot it cooked slower than the dal and vegetables, and I would have to make a frenzied attempt to finish it. In that brief fifteen to twenty minutes between massage and lunch?while Srila Prabhupada bathed, dressed, put on tilaka, and recited his gayatri mantra?I also had to cook the capatis. After his gayatri, Prabhupada would ring his bell and that was it; I had to bring his lunch without a minute's delay. Srutakirti was around to give me some tips, but for a few days Srila Prabhupada tolerated a less-than-average lunch.

I have never experienced such combined anxiety, anticipation and breathless pleasure as I did in preparing Srila Prabhupada's lunch, serving it to him, standing by to see what he would say, and running back and forth to bring hot capatis. The kitchen area in the servant's quarters was disarrayed, full of pots and covered with flour. My mind and senses were completely tense and ready to jump at Prabhupada's command.

Sometimes Panditji would come in and help me prepare the capatis while Prabhupada was eating. Prabhupada liked them round, thin, and biggish. After rolling one on a floured surface, I would pick it up, pat off the flour and put it in a frying pan on medium heat. When the capati stiffened slightly, with air bubbles appearing on its surface, I would flip it over, briefly cook the other side, then remove it from the frying pan with tongs and hold it over a low flame. When it puffed up, I took if off the flame and buttered one side. Each operation had to be done just right.

As Panditji and I took turns running capatis into Prabhupada, he would often make comments. If the capatis or other dishes were not cooked to his satisfaction, he would say something sarcastic like, "It's half-cooked," or "It's burnt." Or if something was all right, he would be pleased and say so. Sometimes I made something I thought was bad, but Prabhupada would like it, or just the opposite. Sometimes he would seem very easy-going and kind no matter what I cooked, and sometimes he would become angry as if my poor cooking were a great calamity. There was no way to take it but to surrender to whatever he did.

One of the first times I cooked lunch, several of the preparations didn't come out at all well. I brought the lunch in with great trepidation. But just at that moment, a devotee from the temple arrived with some samosas that Srutakirti's wife had made at her apartment. Prabhupada ate them all deliciously, and the day was saved.

Whenever Prabhupada ate, I would simply hang on his every word or gesture to see whether he appreciated what I had done. It was no casual matter to wonder and anticipate, "How does he like it?" I was so tensed up I was ready to cry or laugh. If he said a capati was not cooked, I would run back and try to make the next one come out right. I would be sometimes panting in a breathless state, sweating and nervous. Only a devotee of Prabhupada could appreciate that all these symptoms were transcendental. It was no ordinary exchange, because Srila Prabhupada was no ordinary master but a pure devotee of Krishna. After his lunch, Prabhupada would rest for about an hour, and I would clean my room and go downstairs to wash his silver dishes and cups. I could have engaged someone to help me, but I thought I should do it all myself. Washing dishes in the main kitchen of the temple, I would converse with other devotees in a sociable way, but I was in a world of my own. I worked quickly, intent and always hurrying, and I ran back upstairs to the servant's room. I had no time for extended conversations, nor did I have time to talk about what Prabhupada was doing. I felt I had too much to do, but I also refused to share any of the work. I didn't want to shirk my duties as a servant.

But I did have a rather impossible schedule and workload. Prabhupada usually assigned the duties of secretary and servant to two men. But I was both secretary and servant. In addition to tending his personal needs, I read him his mail, took dictation as he replied to each letter, and typed his return letters. Panditji would only perform his duty as Sanskrit editor for Prabhupada's Bhagavatam translations. He otherwise made himself scarce or refused to do anything asked of him.

I was also charged with typing Srila Prabhupada's Bhagavatam dictation and editing the English manuscript. And I was still the G.B.C. secretary of temples in the Mid-west. Whenever I found time, I would run down to the main office and speak on the phone to one of the temple presidents in my zone. In addition, I was also editor-in-chief of Back to Godhead magazine and had to read incoming manuscripts and try to write articles myself. It was all a bit too much.

Prabhupada observed me running here and there trying to organize my program while sometimes forgetting things, and he chided me in a loving, instructive way. He noticed that I had burned a ring on the floor of my room by placing a hot pot there, and he made a brief remark.

Reference: Life with the perfect master - A personal servants account by Satsvarupa Das Goswami

Recently Added

Trending Today