"Who Has Painted This One?"

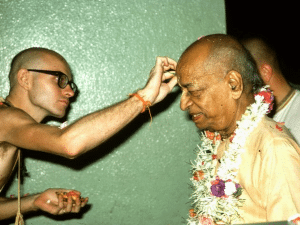

Anakadundubhi dasa: While Srila Prabhupada lived in Mayapur, his routine was punctuated by visits and news from the various fronts in his worldwide campaign against maya. Particularly welcome moments occurred when Prabhupada received advance copies of his books. However, when he received a copy of Srimad-Bhagavatam, Canto 6, Volume 3, with its cover portrait of Lord Sesha receiving the worship from Citraketu and the four Kumaras, Prabhupada looked at it only briefly and then went on with his routine. He went to the roof, where he sat on a straw mat in the sunshine. There his servant massaged him with mustard oil, and then Prabhupada bathed, took prasadam, and rested for an hour in his upstairs room. According to his regular habit, he came down from his room on the roof at about four o'clock in the afternoon and received guests in his main sitting room on the second floor. Anakadundubhi dasa had a small part to play in Srila Prabhupada's daily routine, as each afternoon he brought Prabhupada a fresh afternoon garland of flowers and applied candana paste to Prabhupada's forehead. On the day that the Sixth Canto of the Bhagavatam arrived, Prabhupada took it up again when he came down to his room. While his disciple stood by waiting with the garland and candana paste, Prabhupada began to peruse the book in his usual manner, looking first at the illustrations. Prabhupada suddenly noticed Anakadundubhi and signified with a glance that he could go ahead and put on the garland and the paste. Then Prabhupada continued to look through the book. "Who has painted this?" asked Prabhupada as he looked at the painting of Lord Sesha. "That was done by Parikshit," said Anakadundubhi, who stood looking over Prabhupada's shoulder at the open book in Prabhupada's hands. Prabhupada then turned the page to a plate reproduction of Maha-Vishnu lying in the Causal Ocean, manifesting all the universes from His gigantic form. "Who has painted this one?" asked Prabhupada. "That's by Ranacora dasa," said Anakadundubhi. Prabhupada then began quoting from the Brahma-samhita. yasyaika-nisvasita-kalam athavalambyajivanti loma-vilaja jagad-anda-nathahvishnur mahan sa iha yasya kala-viseshogovindam adi-purusham tam aham bhajami Prabhupada was just about to turn to the next page, when suddenly a drop of the wet candana paste fell from Prabhupada's forehead onto the page. Anakadundubhi became frightened, expecting Prabhupada to reprimand him for making the paste so runny that it had dripped onto the book. But Prabhupada only touched it with his thumbnail and asked, "What is this?" Anakadundubhi explained what it was, but Prabhupada said nothing. Ordinarily the runny paste might have been enough to draw a word of disapproval from Srila Prabhupada, but he was drawn so much into the Bhagavatam that he continued his study of the book, overlooking the spot of sandalwood paste that now adorned the page. Anakadundubhi dasa, interview. A reader may ask, "What is the point of this anecdote?" The "point" may be stated as follows: Srila Prabhupada was so absorbed in appreciating the newly published volume of Krishna's book that he both overlooked a discrepancy caused by his servant and he overlooked that the book now had a spot on it. It is a portrait of Prabhupada in ecstatic concentration. By way of justifying this anecdote as well as others, I would like to state that the real "point" of the anecdote is its charm and the fact that it gives us a glimpse into Prabhupada's life. Whatever allows us to be drawn closely into Prabhupada's presence is itself worthwhile; the Vedic instruction is there blended into Prabhupada's personal presentation of that instruction by his every act. In researching through English literature to find precedents for books in the form of anecdotes, I found an interesting essay, "A Dissertation on Anecdotes," by Isaac D'Israeli, an eighteenth century author. His appreciation of the unique strength of anecdotes can be perfectly applied in the case of anecdotes about Prabhupada. D'Israeli writes that while it is possible for anecdote writers to sometimes write of items too minute or trivial in describing a historic person, if the person is truly illuminating, anything is worthwhile. "For my part," he writes, "I shall be charmed that we have a good life of Homer, or Plato, or Horace, or Virgil, and their equals. It is in these cases that the minutest detail would not fail to interest me." (He states, however, that he is not interested in even the main important facts in the lives of persons who actually lack greatness.) In our case, writing of Srila Prabhupada, we are confident that he is of the greatest stature whether considered humanly or spiritually, so we should be confident that if we nicely tell any anecdote about Prabhupada it will be worthwhile. I have already stated in the Preface to Volume One, however, that considerations of etiquette should be applied in describing the spiritual master. When I have gone ahead and told an anecdote that may possibly be misconstrued, I have tried to explain it more fully in these notes. Before leaving D'Israeli's dissertation on anecdotes, I would like to share a few more of his quotes to help us more appreciate the gain in reading about Prabhupada through the anecdotal medium. While these reflections by an eighteenth century literary gentleman were not intended exclusively for descriptions of the pure devotee of the Lord, we may happily engage them when thinking of anecdotes about Srila Prabhupada. "An intelligent reader frequently discovers (through anecdotes) traits which seem concealed. He does not perceive these faint touches in the broad canvas of the historian, but in those little portraits which have sometimes reached posterity. He acquires more knowledge of individuals by memoirs than by history. In history there is a majesty, which keeps us distant from great men; in memoirs, there is a familiarity which invites us to approach them. In histories, we appear only as one who joins the crowd to see them pass; in memoirs we are like concealed spies, who pause on every little circumstance, and note every little expression. A well chosen anecdote frequently reveals a character more happily than an elaborate delineation, as a glance of lightning will sometimes discover what has escaped us in a full light. We cannot therefore accumulate too great a number of such little facts. It is only the complaint of unreflected minds that we recollect too many anecdotes. Why is human knowledge imperfect but because it does not allow sufficient years to enable us to follow the infinity of nature? Human nature, like a vast machine, is not to be understood by looking on its superficies but by dwelling on its minute springs and little wheels. Let us no more be told that anecdotes are the little objects of a little mind."