My lifelong skepticism

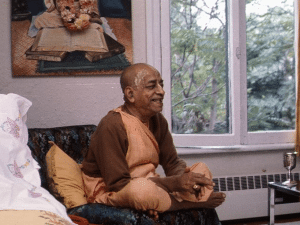

Visakha Devi Dasi: A small group of us were scheduled to go with Prabhupada to meet Kenneth Keating, the U.S. ambassador to India. I'd heard of Keating and was looking forward to photographing him and Prabhupada together. On the morning of the appointment, I was getting my camera, lenses, and film ready when the Delhi temple president asked me to cook breakfast for the devotees. I explained to him this wasn't a good day for me to cook but, to my distress, he failed to see my point and insisted that I cook. Since Prabhupada was so accessible, without much thought I burst into his room and blurted out my difficulty. From his usual vantage point—seated cross-legged on the floor behind a small table—Prabhupada regarded me. Even while I was in the middle of my first sentence I thought, “This is dumb! Why on earth am I bothering Prabhupada with such a petty issue?” And from his expression, it seemed Prabhupada was thinking similarly. I left his room, now doubly flustered, to find that in the meantime the temple president had enlisted someone else to cook.

Relieved, I packed into a car with the others, including Syamasundara and his daughter Sarasvati, and we all drove to the American Embassy where we were graciously welcomed by Keating and his wife. Sitting with them in a posh room in the Embassy, we were each served a tall glass of fresh coconut water as Prabhupada explained to the couple how the body is a dress, just as our clothes are, and that the person, the living force or soul, is within the body, just as a person is within his or her clothes. The soul is massless, invisible, and indivisible, yet more essential than any aspect of our physical nature. It is our identity.

As I photographed I was surprised to hear Mrs. Keating say, “That’s very interesting. I believe in the transmigration of the soul.”

“It is a fact,” Prabhupada said. “Just like this child..." he said as he indicated Sarasvati, “...is transmigrating from one body, one kind of body to another body. So in the same way, when I give up this body I transmigrate to another body. This is the science. Unfortunately, there is no university, no education, no culture of this great science.”

Prabhupada pointed out how the soul’s nature is to serve and therefore everyone is serving, whether one’s boss or family or pet or oneself. He said, “Suppose I say that I don’t serve. That is not possible. That being our constitutional position then, just like my finger, it is serving, always, sometimes doing like that, sometimes doing like that, sometimes doing like that. The finger’s business is to serve. As part and parcel of my body, the finger’s business is to serve the whole body. Similarly, we are part and parcel of God. Our essential business is to serve God. How do you find this argument? Do you refute this argument?”

Again, Mrs. Keating surprised me with her acceptance. She said, “You serve and you share.”

Prabhupada: “Yes. By serving I share. Just like this milk. The hand helps me, brings it here. I drink, and as soon I drank, the benefit is shared by all the parts of the body. Is it not?”

Ambassador Keating: “That’s true.”

Prabhupada: “Just like you pour water in the root of the tree. The energy immediately, I mean to say, distributed to the leaves, to the tree, to the flowers, to the fruits, everything, immediately. Similarly, there must be something which is the root of everything. That is God."

Prabhupada’s confidence seemed effortless and his words, resonating within me, encompassed layers of common sense as it stretched those layers too. Hearing from him I could imagine I was a spiritual being—a soul—inhabiting a body. And I could feel why my mother’s answer to my question a decade earlier, “What will happen to me after I die?” had frustrated me and left me empty. (“Nothing happens. You're buried or cremated. That’s it,” she'd said). I wanted to live a life built on the premise of the soul's presence. That premise made sense out of life; it gave meaning and shelter to my existence. And it just could be true.

I was thrilled to hear Prabhupada speak the basic tenets of the philosophy and see him interact with people; as far as I could tell, he didn't calculate, plot, or scheme, but stirred their consciousness—my consciousness—with the clarity of his message and his simple mood, full of vigor and emotion and faith.

I was enamored of a 76-year-old who was four inches shorter than me and had no material assets! How could I ever explain such a thing to my friends and family in the States? How could I explain it to myself? Yet as strange as it looked and as unexpected as it was, not only did it feel completely natural but I wanted it to happen. I'd wandered into a traditional guru-disciple relationship of mutual service and love and was held by its possibilities, by how it opened me up. After all, I thought, ultimately what is love but the way a person makes me feel, the intense affection I have for that person; love is not the proper subject of arguments.

As Prabhupada’s teachings and his very being filled my gaping vacuum, inside me there was a whoosh, the whoosh of newly found reasoning and logic, the whoosh of fresh analysis and analogy, the whoosh of spiritual duty, and most of all, the whoosh of the possibility of love for God, the beautiful, delightful, playful person Krishna. Krishna was complete in himself yet yearned for my love as I, underneath everything else, yearned to love him. White water rapids of hope had swept me up and were carrying me downstream toward an ocean, my head bobbing on their promise.

Prabhupada had entered a barely noticeable clear spot in my heart and stirred something that affected me as nothing else in my life had. What had happened to my lifelong skepticism? Would my feelings for him last? Was I being duped?

After the meeting, Keating accompanied us to our waiting ambassador and watched politely as Prabhupada sat in the front passenger seat next to Syamasundara, the driver, and the other seven of us crammed into a back seat meant for four. I was sitting on someone’s knees, the back of my neck pressed against the car's ceiling and my elbows and camera case pinned in by the people wedged beside me. We were young and products of the 60s and besides, stuffing as many people in a vehicle as humanly possible was quite Indian. Prabhupada and Keating continued chatting.