Brahmanas' criticism

Visakha Devi Dasi: In Madras, caste brahmanas dominated religious and governmental posts and excluded non-brahmanas regardless of their qualifications. Prabhupada adamantly challenged this caste system that, he said, had destroyed Indian culture. According to the Bhagavad-gita, Prabhupada said, "One’s occupation is not based on one’s birth but on one’s proclivity." In Krishna’s words, one’s work is determined by one’s qualities and activities. not by birth.

For an American like me, the brahmanas' position was untenable. The birth was secondary; why should my career be determined by the family I was born into? But for them, birth was not secondary. Birth was all-important, and one accepted it as divinely ordained fate and conducted one’s life accordingly regardless of one’s qualities or activities. With this philosophy, it was easy to take one’s birth in a high caste as well-deserved, and if one lacked knowledge, as a license to oppress lower castes. That mood of superiority and oppression, however, was the antithesis of an actual brahmana’s mood: an actual brahmana was humble and wanted to elevate others, not repress and oppress them; an actual brahmana wanted others to be all they could be for God’s pleasure.

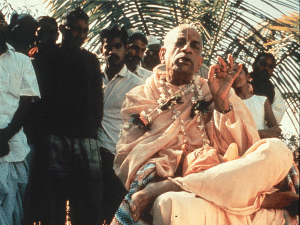

The brahmanas in Madras criticized Prabhupada for creating brahmanas from lowborn, unqualified westerners. Prabhupada replied, “This is not my philosophy. I am simply acting on Krishna’s words in Bhagavad-gita. These students have given up their bad habits and come to the brahminical standard, so they are qualified and must be accepted as brahmanas.”

The Bhagavad-gita’s teachings, I understood, were Prabhupada’s warp and weft, his grounding, the bottomless sacred well where he drew his strength and courage. Bhagavad-gita was where his spiritual master and the spiritual masters before him had also drawn divine potency. I couldn't fathom how much the Gita’s 700 verses contained, but I was moved by their antiquity and the ease with which Prabhupada drew on their wisdom.