Prabhupada in straw thatched cottage

Visakha Devi Dasi: The only cement structures on our newly acquired three-acre Mayapur property were a small storage building and an even smaller building for the enchanting, two-foot-high, brilliant, brass Deities of Sri Sri Radha Madhava, as well as a captivatingly graceful, wood-carved Deity of Sri Caitanya. Their priest, a survivor of the early Calcutta days, was Jananivasa, a good-natured Englishman who had been Revatinandana Swami’s assistant and had moved to Mayapur to focus entirely on serving the Deities.

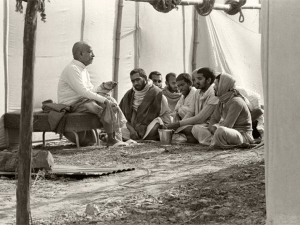

Prabhupada was quartered in a straw-and-mud thatched cottage near the main road. He told us, “You can build me the biggest palace, but still, I'd prefer to live here.” When I went inside I could see why: it was cool and tranquil and seemed built of virtue and purity.

The devotees’ quarters were two separate large tents, one for the men and one for the women—the women’s complete with 24-hour fluorescent lighting (we never did find the “off” switch for those lights). Mayapur was infested with mosquitoes, and from dusk on our first day we were fending off hordes of oversized, undeterred attackers. My friend Srimati and I were on the side of the women’s tent that was just 10 feet from the open chattai window in Prabhupada’s cottage, and while still under my mosquito net hours before sunrise on our first morning in Mayapur, I heard Prabhupada’s voice in the fresh, calm air. He was speaking into his dictaphone, translating the Sanskrit scriptures into English and giving purports based both on commentaries from previous spiritual authorities and his own realizations. These recordings, which he made every morning wherever he was, were later transcribed, typeset, and printed as the Srimad-Bhagavatam.

I could not imagine Prabhupada's daily task of harnessing impetuous, impassioned, untrained young men and women to international society with a selfless spiritual mission. In 1969, Prabhupada had written one of his disciples, “If all problems come to me, even personal problems, then it becomes a heavy task for me. I received your letter, full of problems; Gargamuni’s, full of problems; Rayarama’s, full of problems, and similarly ISKCON Media’s, full of problems. If everyone's problems are sent to me, then who will solve my problems? I have divided these departments to solve problems, but if in the end they are all sent to me and I have to tackle, then just imagine what is my position? The best thing would be to stop all activities and simply chant Hare Krishna.”

How restoring it must have been for Prabhupada, in the silent mornings long before the rest of us—his problems—arose, to gradually fulfill his guru's desire for spiritual literature and, in solitary communion, to deeply reflect on Krishna and his energies. Prabhupada’s translations and commentaries on the Srimad-Bhagavatam, “the ripened fruit of all scriptures,” were a daily flowering of grace offered to a world in critical need of that grace. Lying on my side under the glaring fluorescent lights listening to his voice, laden with Krishna, I felt a sanctuary in the strength of his determination, in his devotion to his divine duty. My feelings soared and before I knew what was happening my eyes were moist. I realized how little I normally felt, how numb I was to what he gave one small person—me.