We shall call our society ISKCON

“We shall call our society ‘ISKCON.’” Prabhupada laughed playfully when he first coined the acronym.

He had initiated the legal work of incorporation that spring, while still living on the Bowery. But even before its legal beginning, Prabhupada had been talking about his “International Society for Krishna Consciousness,” and so it had appeared in letters to India and in The Village Voice. A friend had suggested a title that would sound more familiar to Westerners, “International Society for God Consciousness,” but Prabhupada had insisted: “Krishna Consciousness.” “God” was a vague term, whereas “Krishna” was exact and scientific; “God consciousness” was spiritually weaker, less personal. And if Westerners didn’t know that Krishna was God, then the International Society for Krishna Consciousness would tell them, by spreading His glories “in every town and village.”

“Krishna consciousness” was Prabhupada’s own rendering of a phrase from Srila Rupa Goswami’s Padyavali, written in the sixteenth century. Krsna-bhakti-rasa-bhavita. “to be absorbed in the mellow taste of executing devotional service to Krishna.”

But to register ISKCON legally as a nonprofit, tax-exempt religion required money and a lawyer. Carl Yeargens had already had some experience in forming a religious organization, and when he had met Prabhupada on the Bowery he had agreed to help. He had contacted his lawyer, a young Jewish man named Stephen Goldsmith.

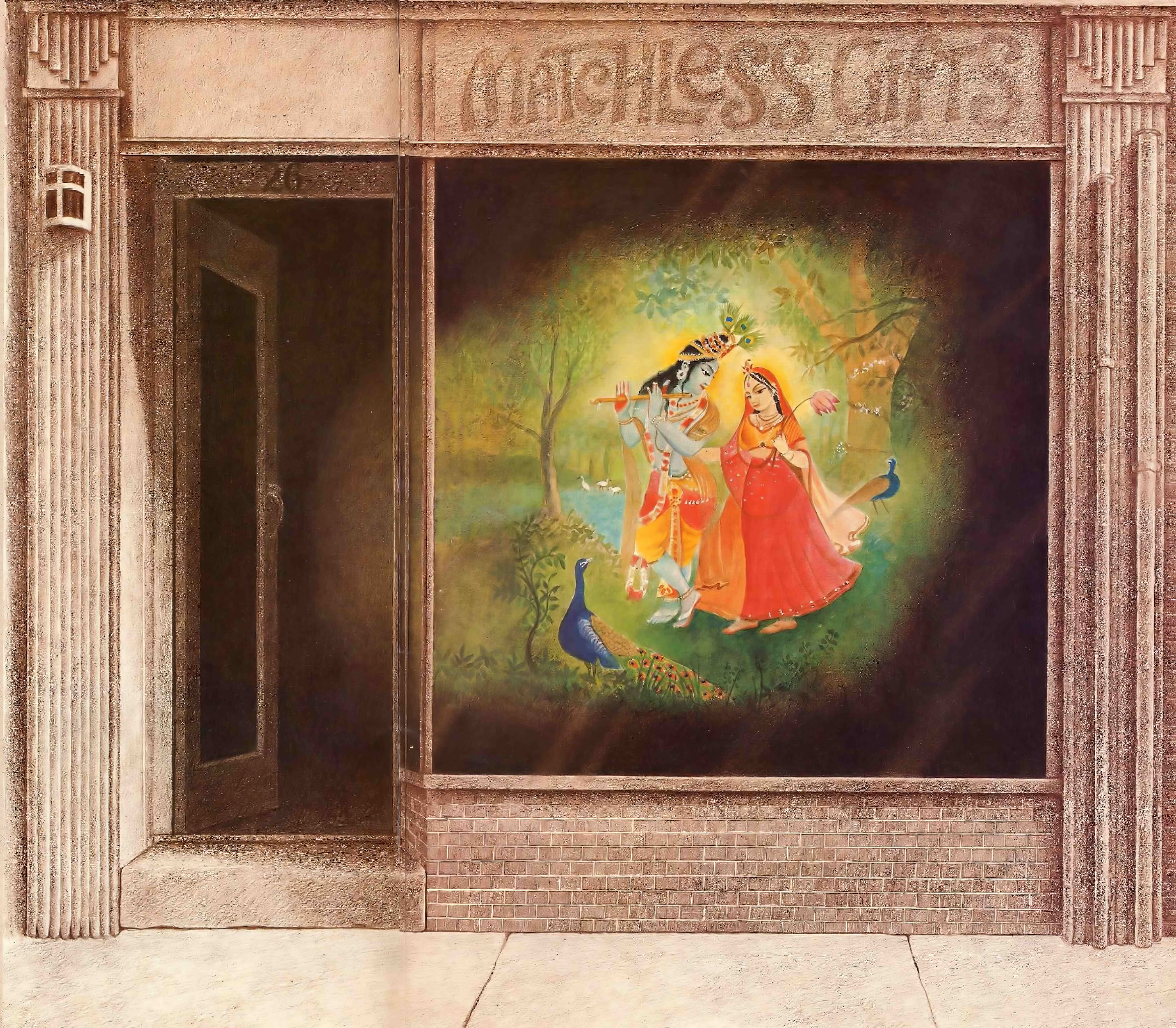

Stephen Goldsmith had a wife and two children and an office on Park Avenue, yet he maintained an interest in spirituality. When Carl told him about Prabhupada’s plans, he was immediately fascinated by the idea of setting up a religious corporation for an Indian swami. He visited Prabhupada at 26 Second Avenue, and they discussed incorporation, tax exemption, Prabhupada’s immigration status — and Krishna consciousness. Mr. Goldsmith visited Prabhupada several times. Once he brought his children, who liked the “soup” Prabhupada cooked. He began attending the evening lectures, where he was often the only nonhippie member of the congregation. One evening, having completed all the legal groundwork and being ready to complete the procedures for incorporation, Mr. Goldsmith came to Prabhupada’s lecture and kirtana to get signatures from the trustees for the new society.

July 11. Prabhupada is lecturing.

Mr. Goldsmith, wearing slacks and a shirt and tie, sits on the floor near the door, listening earnestly to the lecture, despite the distracting noises from the neighborhood.

Prabhupada has been explaining how scholars mislead innocent people with nondevotional interpretations of the Bhagavad-gita. Now, in recognition of the attorney’s respectable presence, and as if to catch up Mr. Goldsmith’s attention better, Prabhupada introduces him into the subject of the talk.

I will give you a practical example of how things are misinterpreted. Just like our president, Mr. Goldsmith, he knows that expert lawyers, by interpretation, can do so many things. When I was in Calcutta, there was a rent tax passed by the government, and some expert lawyer changed the whole thing by his interpretation. The government had to reenact a whole law, because their purpose was foiled by the interpretation of this lawyer. So we are not out for foiling the purpose of Krishna, for which the Bhagavad-gita was spoken. But unauthorized persons are trying to foil the purpose of Krishna. Therefore, that is unauthorized.

All right, Mr. Goldsmith, you can ask anything.

Mr. Goldsmith stands, and to the surprise of the people gathered, he makes a short announcement asking for signers on an incorporation document for the Swami’s new religious movement.

Prabhupada: They are present here. You can take the addresses now.

Mr. Goldsmith: I can take them now, yes.

Prabhupada: Yes, you can. Bill, you can give your address. And Raphael, you can give yours. And Don.... Raymond. ... Mr. Greene.

As the meeting breaks up, those called to sign as trustees come forward, standing around in the little storefront, waiting to leaf passively through the pages the lawyer has produced from his thin attache, and to sign as he directs. Yet not a soul among them is committed to Krishna consciousness. The lawyer meets his quota of signers, but they’re merely a handful of sympathizers who feel enough reverence toward the Swami to want to help him.

The first trustees, who will hold office for a year, “until the first annual meeting of the corporation,” are Michael Grant (who puts down his name and address without reading the document), Mike’s girlfriend Jan, and James Greene. No one seriously intends to undertake any formal duties as trustee of the religious society, but they are happy to help the Swami by signing his fledgling society into legal existence.

According to law, a second group of trustees will assume office for the second year. They are Paul Gardiner, Roy, and Don. The trustees for the third year of office are Carl Yeargens, Bill Epstein, and Raphael.

No one knows exactly what the half-dozen legal-sized typed pages mean, except that “Swamiji is forming a society.” Why?

For tax exemption, in case someone gives a big donation, and for other benefits an official religious society might receive.

But these purposes hardly seem urgent or even relevant to the present situation in the little storefront. Who’s going to make donations? Except maybe for Mr. Goldsmith, who has any money?

But Prabhupada is planning for the future, and he’s planning for much more than just tax exemptions. He is trying to serve his spiritual predecessors and fulfill the scriptural prediction of a spiritual movement that is to flourish for ten thousand years in the midst of the Age of Kali. Within the vast Kali Age (a period that is to last 432,000 years), the 1960s are an insignificant moment.

The Vedas describe that the time of the universe revolves through a cycle of four “seasons,” or yugas, and Kali-yuga is the worst of times, in which all spiritual qualities of men diminish, until humanity is finally reduced to a bestial civilization devoid of human decency. Yet for ten thousand years after the advent of Lord Caitanya there is the possibility of a Golden Age of spiritual life, an eddy that runs against the current of Kali-yuga. With a vision that soars off to the end of the millennium and far beyond, and yet with his two feet planted solidly on Second Avenue, Srila Prabhupada has begun an International Society for Krishna Consciousness. He has many practical responsibilities: he has to pay the rent, and he has to incorporate his society and pave the way for a thriving worldwide congregation of devotees. Somehow, he doesn’t see his extremely reduced present situation as a deterrent from the greater scope of his divine mission. He knows that everything depends on Krishna, so whether he succeeds or fails is all up to the Supreme. He has only to try.

The Seven Purposes of ISKCON

The purposes stated within ISKCON’s articles of incorporation reveal Prabhupada’s thinking. They are seven points, similar to those given in the Prospectus for the League of Devotees he had formed in Jhansi, India, in 1953. That attempt had been unsuccessful, yet his purposes remained unchanged.

Regardless of how ISKCON’s charter members regarded the Society’s purposes, Srila Prabhupada saw them as imminent realities. As Mr. Ruben, the subway conductor who had met Prabhupada on a Manhattan park bench in 1965, remembers, “He seemed to know that he would have temples filled up with devotees. ‘There are temples and books,’ he said. ‘They are existing, they are there, but the time is separating us from them.’”