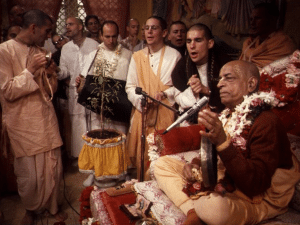

Sri mridanga.

Other devotees have come to India on Prabhupada's request to learn the ancient art of making mridangas. Ishan has answered the call and is studying along with several other western men. Ishan: I was in Toronto when Srila Prabhupada sent out a notice to all temple presidents that mridanga making was a dying art. There was no more pride in it. They were embarrassed to take up these trades. I could see that when I was there. So Prabhupada wanted his men to come and learn. Jagadish was our president and I found a notice among papers on his desk, un-posted, that said, "Srila Prabhupada wants men to go to Mayapur to learn to make drums." I said to Jagadish, "I saw that notice and I want to go to Mayapur and make drums." He said, "Fine." So I collected the money and went to India. Among the group of devotees who have come to learn drum making, most cannot get the hang of this Bengali craft. Some of them don't even last two days in Mayapur and are back on a plane to the West. But Ishan is more a Bengali than an American, and he becomes the apprentice for the mridanga mistri. He serves him and brings the man prasadam. He sweeps the dirt out of the bamboo hut where the drums are made. In return the mistri takes care of Ishan like a father. He can't speak English and Ishan can't speak Bengali, so he simply draws pictures on the dirt floor of the hut with a stick. One day a man comes who is a translator. The western devotees frequently ask, "Why does he do it this way?" Ishan glances at them as he continues cleaning the hut, or scraping the hair off a new hide, or stretching a new one in the field outside the door. When the translator questions the mistri, he simply looks up, pauses, and replies in Bengali, "My father did it that way."

After a week has passed, the mridanga mistri draws a picture of a map of the world on the dirt floor. He points to the various devotees who have come to learn, sitting in the hut with their notebooks, and he says, "mridanga mistri nei," as he points to each of them one by one. Then he points to Ishan and says, "Ishan Prabhu, mridanga mistri." Ishan: I loved him and that was the difference, I think, because you only give your secrets to someone who loves you. And I served him. Not because I wanted the secrets; it was natural. I really loved this man. He was barely over five feet and very thin, with jet black hair, and about 65 years of age. He did a few yoga asanas to stretch before he began his work. And when he was tired, he would put a cloth on the floor of the hut and just curl up and go to sleep, saying, "Acha, resting." Then after 45 minutes he would rise, take some water to wash his face and hands, and back to work. He taught me a lot about being just natural. Actually, there were two men. A different man taught me how to make a clay shell. I would have to clean his clay. We'd dig it out of the ground and take every piece of grass out of it until it was smooth. That was my job. Yogin Pal was the clay man and Jotin Da was the mridanga man. He would always apologize to the mridanga for having to put his foot on it when tightening the straps. He had a very devotional attitude and always referred to the drum as "Sri mridanga."